Innovation activity depends on the allocation between productive

activity and unproductive activity in entrepreneur (Baumol, 1990). This allocation

is determined by what payoff available in society. One of the pay-offs determined by the income after tax

derived from the innovative activity that

received by the entrepreneur. Thus, the lousy

tax policy that creates punitive taxation

will undermine innovative activity (Mitchell, 2018).

Nowadays Indonesian

entrepreneur prefers to invest in another type of investment than invest in

intellectual property. It is because being an investor in for example loan and

stock derived higher after-tax payoff. It resulted from different treatment of withholding tax, because income derived from innovative activity is taxed at a higher rate. Thus,

the marginal tax rate differences create

disincentives for innovation (Aghion et al.,

2016).

Moreover, the provision in tax audit offers unbalance treatment for innovative activity, create higher

uncertainty of audit result for the taxpayer

(Caballé and Panadés, 2005). The reason is

that the high withholding tax tariff will trigger overpayment position at the end of the fiscal year and leads to taxpayer’s restitution that is subject to

tax audit. In contrast, income from stock investment is taxed at a flat and final

rate, there will be no overpayment or audit consequences, and for income from a

loan, investment has loopholes of not

being taxed and audited.

As a result, from 2017 until 2018, there were two issues happened in Indonesia. First,

is the protest from creativity worker over the high rate taxation on royalty

income, they are questioning about the

disincentives for people to innovate. Second, the

fast-growing number of the loan shark investors and the bad-debt that they created, one of the

reason is that the poor regulation on the financial

market outside the banking system. This event even made Indonesia Financial

Service Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, OJK) to create regulation

specifically to curb loan shark and the effects it created.

The question is why this phenomenon happens? Why Indonesian less

invest in innovative activity? This paper tries

to explain from the perspective of a tax

institution’s role in determining the rule of the game of individual taxpayer

and shaping their innovative behaviour through

the mechanism of tax incentives. This paper argues that strict taxation

on innovation that includes high

withholding tax rate and audit treatment reduces

the level of innovation. This paper excludes the tax treatment on active income since it does not subject to

differential withholding tax.

This paper consists of

several parts. Part 1 deals with the introduction

of the problem and current condition in

Indonesia. Part 2 provides evidence of innovation compare Indonesia’s tax

regime on innovation with ASEAN countries. Part 3 explains about strict

taxation and differential tax rate in Indonesia’s domestic tax regulation. Part

4 explains the theoretical model of

allocation of innovative activity. Part 5 deals with an analytical framework to understand institutional change. Last but

not least, part 6 explains the conclusion and suggestion.

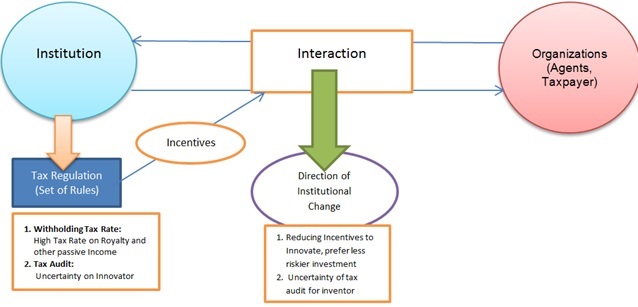

2. Evidence from ASEAN Countries

2.1. Innovation Data

Between ASEAN Countries,

Indonesia is considered left behind from

other countries regarding intellectual

property (“IP”) according to the data from the World

Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The data shows that patent

registration in Indonesia in 2016 is 1,154 patents, while Singapore has 6,722,

Thailand has 1,601 and Malaysia 1,963. Indonesia position is only better than

the Philippine and Vietnam which recorded

557 and 633 respectively.

Figure 1 Patent Registration across ASEAN

2.2. Royalty Income Withholding Tax

The right to derive

income from the asset (Alston and Mueller, 2008) are one factor

that determines the full set of property rights. The payoff from innovation is royalty. Several factors influence the payoff, first is

the royalty rate that determined by the market mechanism and the value of

intellectual property. Second is the withholding tax rate imposed in royalty

income. This paper will focus on the second factor which is the withholding tax

rate.

As a comparison, the

table below shows the difference in

withholding tax rate ASEAN countries. Singapore and Malaysia, the 2 (two) most

innovative countries in ASEAN implement withholding tax rate on royalty 0%,

while Thailand implements 3%. In contrast, Indonesia and Philippine have the highest royalty rate between that country which 15%. A particular case for

Vietnam, which has 10% royalty rates, lower than Indonesia and Philippines, but

the patent registered has lower in number.

Source:

PWC Accounting Firm (www.taxsummaries.pwc.com)

Considering the data from

the table above, Singapore, Malaysia, and

Thailand as the most productive countries in ASEAN in term of patent produced

have one thing in common. They have low withholding tax rate on royalty income.

The lower the tariff is, the higher the

payoff received by the innovator.

3. Indonesia’s Strict Taxation: Withholding Tax and Audit Treatment

Since the first modernisation on Indonesia’s income tax

regulation that took place in 1983 (Income Tax Act Number 7 of 1983), there

were four amendments. The first amendment took place in 1991 by the enactment of Income Tax Act Number 7 of 1991.

The Second amendment took place under Income Tax Regulation Number 10 1994. The

Third amendment took place under Income Tax Regulation Number 17 2010. The last Amendment was under Income Tax

Regulation Number 36 of 1994.

In every amendment, each

amendment has a specific aim which the

goal is to inlining tax regulation with

the economic and business condition. For example, the last amendment was to

provide an equal level playing field in

the banking industry. However, regarding

taxation on royalty income, there was no

change of the tax provision ever since the first Income Tax Act enacted.

Under the withholding tax regime, passive income which

consists of Dividend, Interest, and Royalty has a different rate and audit treatment. From entrepreneur perspective,

the differential rate and audit treatment create a condition where one activity is more favourable than the others.

Consider an entrepreneur,

who has IDR 200,000,000 to invest. He has three choices to generate more money.

First is to invest in stock market and receive dividend income, second is to

give a loan to other people and receive

interest income, and third to invest in intellectual property by conducting

research and come out with some innovation, register the IP and received the

royalty income. From the tax perspective, those choices will result in

different outcomes as follows:

Table 2 Differential Tax Treatment

|

| Indonesian Differential Tax Treatment (www.taxedu.web.id) |

Source:

Author

From the table above, we

can conclude that the royalty income is subject to two different tax treatments

compared to the other passive income. First at the level of the transaction

when the payment received, royalty income is subject to 15% withholding tax rate, resulted

in higher effective tax rate compared to the others. In contrast,

Dividend income only taxed at 10%, and interest income has the opportunity to avoid withholding tax by

structuring the loan contracts.

Second, related to audit

treatment. The audit triggered at the end

of the fiscal year when the taxpayer has

to calculate personal income tax. The withholding tax rate on the royalty

income will trigger tax audit since personal income tax rate layer are lower

than withholding tax, resulted in overpayment position that subjects to tax audit. The uncertainty of the

probability of being audited reduce expected payoff of the taxpayer (Snow and Warren, 2007). While, interest income and dividend income do

create overpayment position. Dividend income is considered low tax risk, since

the application of final and flat tax rate. However, the interest and royalty

income is subject to general taxation at the end of the fiscal

year. Existing regulation state that interest income is exempted from withholding tax if received from the individual

borrower, this explains why more people are becoming loan investor. But, the enforcement in the financial sector is

not strict and too many loopholes that lead to taxpayer rent-seeking behaviour.

4. Theoretical Model: How Tax Affect Innovation

To understand how royalty tax influences innovation activity, we

should examine how interaction between

royalty tax and other investment tax. Using an investment

allocation model used by Blonigen (Blonigen and Piger, 2014), we consider an investor who has two

option of investment.

Assume, investors have a total

amount of capital,

Capital

= K

They have two option;

either to invest in innovation or to invest in other investment. Assume R

represents the amount of capital invested

in innovation,

R

≤ K

The rate of return in

other investment equal to:

r

= r(K - R)

Moreover,

the rate of return in innovation equal to:

r*

= r(R)

With taxes rate as

consideration, the investor will equalize

income after tax. Hence, the amount of R is

determined and depended on (1

- t)r = (1 - t*)r*. t denotes the effective tax rates of other

investment and t*

denotes tax in innovation activity.

(1

- t)r = (1 - t*)r

Hence, the optimal

allocation of innovation, R, depends on the differential

tax rates imposed on the types of investment.

t

= t(K - R; x) and t* = t(R)

Hence the allocation of

innovative activity will be:

5. Analytical Framework

5.1. How Tax Regulation affects Innovation

Institution

is the rule of the game that devised by human

to shapes human interaction (North, 1994). Institution will create incentives in the form

of political, social and economic incentives. The significant role of institution for the society is to lower the

uncertainty and establish stability in human interaction, although the stability that institution does not

necessarily mean efficiency. Nevertheless, together with other factors

such as stock of knowledge and demographic, institution determine the economic

growth of the nations.

The critical role that institution takes place is

through the enactment of laws, regulations,

conventions, norms, contracts, and so forth.

Those instruments are continuously altering the choice available in the society

(Greif, 2006). By providing

incentives and constraints in the choices available, the society behaviour

will react to incentives and avoid disincentives. Through organization, an economic agent in society interacts with set or rules enacted by

the institution to respond to the

incentives, and in the long run, will

result in institutional change. One of regulation that shapes the incentives is

tax regulation which set the rule of the payoff of innovative activity.

In Indonesia, when

innovator invents or innovates something, they should register the

IP to Directorate General of Intellectual Property Rights (DGIP)

of Indonesia. After that, it depends on the inventor whether they want to

exploit it themselves commercially, or to

license it to other party and generate royalty income. Royalty income is

subject to tax are under Indonesia’s income taxation regulation. The taxation

treatment to royalty income is the determining

factor for taxpayer’s incentives to innovate. Since tax also reduce the profit,

as consequences for alterations from informal to formal form of property rights

(Alston and Mueller, 2008).

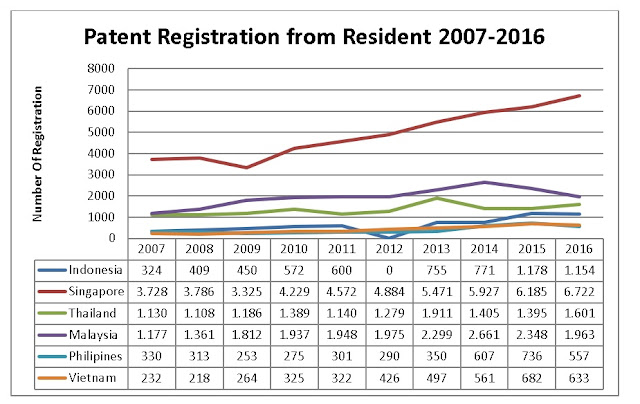

Figure 2 Institutional Framework

|

| Institutional Framework (www.taxedu.web.id) |

Source:

Author

From the picture above,

the tax institution mainly focuses on two

aspects. First is the determination of

the withholding tax rate, second is about the tax audit consequences. Those two

instruments determine the incentives scheme in Indonesia’s tax environment.

On the

other

hand, a collective agent that consists of taxpayers establishes organization to

react to those set of rules and interact with those rules in the market. In the

long run, the tax rules determine the direction of institutional changes. This institutional change depends on the taxation act (high-level

regulation) and on how the taxpayer responds to the incentives of the rules (Kingston and Caballero, 2009). The willingness and capacity to conduct innovative activities

although the indeterminate forthcoming is mostly reliant on the setting that created

by the institutional framework (North, 1992). Therefore, Government through

public policy has a vital role in providing certainties and predictability by

establishing formal rules (for example tax rule) to enable the learning development

and to encourage creative capacity of the entrepreneur (Song and Simpson, 2018).

Mitchel observed that one

percentage point increase in individual tax, decrease the likelihood of

innovation (patenting) by 0.63 percentage point in the next three years (Mitchell, 2018). He also argues that one percentage point increase in

tax leads to a decrease in patent

registration by 1.1% and decrease the number

of citation (research paper) by 1.4%-1.7%. He also points out that tax should

be as low as possible to nurture innovation.

Clemens also finds that the amount of taxes will influence

the quality and the location of innovation (Clemens, 2008). He finds out that tax has intensive and extensive decision to influence the mobility of

inventor and their decision on location.

Given

the existing tax rules in Indonesia creating an unfavourable environment for

innovation, as a result, reducing incentives to innovate and influence taxpayer

to choose another kind of investment than intellectual property, affecting

long-term growth since incentives to acquire innovation (essential factor for

economic growth) was distorted by monetary rewards of tax system (North, 1994). Hence, the high tax rate hurts innovative output,

while tax decreases have a positive impact on innovation (Atanassov and Liu, 2014). Furthermore, taxes have

significant adverse effects on

the quantity and quality of innovation (Akcigit et al.,

2018).

5.2. Game Theoretical Framework in Analyzing Taxpayer Response

This paper develops a simple

theoretical framework to determine the direction

of institutional change in entrepreneur innovation as a response to strict taxation

on innovation. In addition to that, the framework is useful to explain the

loan-shark phenomenon and lower innovation in Indonesia.

Consider the game of

innovation and taxation. The game consists

of player 1 (individual entrepreneur taxpayer) and player 2 (tax institution as

government representative). The strategy of player 1 is either to invest in

innovation or not to invest in innovation (invest in other types of investment,

for example, loan). The strategy of

player 2 is to impose strict taxation (high tax rate and audit) on innovation

or to impose loose taxation (low tax rate and no audit) to boost innovation.

The payoff of player 2 is tax revenues as a result from player 1 action. The

payoff function is modified from Payoff

Matrix of Corruption-Investment Game (Dartanto, 2010) described in the

table below:

Table 3 Game Theoretical Framework

|

| Game Theory for Innovation (www.taxedu.web.id) |

Source:

Author

From the taxpayer

perspective, Let R is royalty income, A

denotes audit risk resulted from overpayment. I is the income from other investment other than innovation. X denotes the incentives of not being

audited and taxed at a lower level, r denotes rent-seeking activity to exploit loopholes in financial and tax regulation,

where k denotes knowledge from

innovation. From the tax institution perspective, PIT denotes tax revenue from personal income tax rate, where WHT denotes tax revenue from withholding

tax rate. TA denotes tax revenues

from the audit process, IP denotes Intellectual property

resulted from innovative activity.

Assume that R = I, r < k, and IP > (TA +

PIT + WHT). The ideal condition is that when government impose loose

taxation in innovation and receive payoff on PIT + IP, and taxpayer receive full R and incentive X and

knowledge k. However, what happens now is that strict taxation in

innovation resulted in not invest in innovation in Nash equilibrium. Government

payoff is only personal income tax PIT,

and taxpayer payoff is income from other investment than innovation I (interest) and incentives of not being

audited X, and r rent-seeking of loan-shark

from exploiting loopholes in tax and financial regulation. This equilibrium

explained the phenomenon on what happened

in Indonesia right now.

Indeed strict taxation derives maximum payoff for tax revenue.

However, the government mistake is solely too much focus on tax revenue rather

than accumulation in intellectual property.

6. Conclusion and Suggestion

If the institution

rewards innovative activities, then

taxpayer engage more in innovation (North, 1994). However, tax

institution in Indonesia does not provide enough incentives for innovation.

Thus the set of rules that influence critical changes in the economy through the allocation of entrepreneurial resources (Baumol, 1990). In Indonesia,

the symptoms are apparent, lower

innovation, and high rent seeking through financial market become the direction

of institutional change.

Indonesia’s Tax

institution should change by providing balanced incentives to kick-start the

innovation. Since nowadays, the capacity and willingness to conduct innovation are

hampered by the institutional framework (North, 1992), primarily tax institution.

Economic growth should be

the focus rather than tax revenues, Indonesia should avoid an environment where designed by a destructive

ruler which objective is only to maximise

tax revenue, rather than economic growth (North, 1981). Since innovation

has a significant role as an engine of economic growth (Acemoglu, 2015), the environment

should encourage creative activity and

innovation in any field to direct economic

growth. Since the speed of economic growth depends on the speed of learning, however the direction

of the growth depends on the expected payoffs in acquiring different kinds of

knowledge (North, 1994). That is why incentives structures need to be modified.

Maybe some people say

that the tax regulation does not have to adjust to the economic change, but the

trigger of changes should come from the need of the society. Thus, considering

what happens in Indonesia now, it is crucial that tax regulation should change.

Reference

Acemoglu, D. (2015) ‘Why nations fail?’, Pakistan Development Review. doi: 10.3935/rsp.v21i3.1238.Aghion, P. et al. (2016) ‘Taxation, Corruption , and Growth Taxation , Corruption , and Growth’, Harvard Business Shool.

Akcigit, U. et al. (2018) ‘Taxation and Innovation in the 20Th Century’.

Alston, L. J. and Mueller, B. (2008) ‘Property Rights and the State’, Handbook of New Institutional Economics, pp. 573–590. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69305-5_23.

Atanassov, J. and Liu, X. (2014) ‘Corporate Income Taxes , Tax Avoidance and Innovation’, Working Paper.

Baumol, W. J. (1990) ‘Entrereneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive’, Journal of Political Economics, 98(5), pp. 893–921.

Blonigen, B. A. and Piger, J. (2014) ‘Determinants of foreign direct investment’, Canadian Journal of Economics. doi: 10.1111/caje.12091.

Caballé, J. and Panadés, J. (2005) ‘Cost uncertainty and taxpayer compliance’, International Tax and Public Finance, 12(3), pp. 239–263. doi: 10.1007/s10797-005-0490-z.

Clemens, J. (2008) ‘The Impact and Cost of Taxation in Canada: The Case for Flat Tax Reform’, Fraser Institute Vancouver, p. 208. Available at: http://books.google.com/books?id=QBdfxA8jTvkC.

Dartanto, T. (2010) ‘The relationship between corruption and public investment at the municipalities’ level in Indonesia’, China-USA Bussiness Review, 9(8).

Greif, A. (2006) ‘Instutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade’, Cambridge University Press, pp. 379–405.

Kingston, C. and Caballero, G. (2009) ‘Comparing theories of institutional change’, Journal of Institutional Economics, 5(02), p. 151. doi: 10.1017/S1744137409001283.

Mitchell, D. J. (2018) ‘High Tax Rates Hurt Innovation and Prosperity , New Data Suggest’, pp. 1–10.

North, D. C. (1981) ‘Structure and Change in Economic History’, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 87(1), pp. 131–159.

North, D. C. (1992) Transaction Cost, Institutions, and Economic Growth, International Center For Economic Growth. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.1987.tb00750.x.

North, D. C. (1994) ‘Economic Performance Through Time’, The American Economic Review, 84(3), pp. 359–368.

Snow, A. and Warren, R. S. (2007) Audit uncertainty, bayesian updating, and tax evasion, Public Finance Review. doi: 10.1177/1091142107299609.

Song, L. and Simpson, C. (2018) ‘Linking “adaptive efficiency” with the basic market functions: A new analytical perspective for institution and policy analysis’, Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, (April), pp. 1–14. doi: 10.1002/app5.249.

http://taxsummaries.pwc.com/ID/Withholding-tax-(WHT)-rates

http://www.patenindonesia.com/?p=784#more-784

http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/

No comments:

Post a Comment